Building resilient leaders

November 21, 2023

After nearly 10 years, Steve Noah ’71 has fulfilled his dream of helping Wartburg College students experience the heartache and restoration of Rwanda firsthand.

Noah, who served in advancement at Iowa State University and William Penn University from 2002 until his retirement in 2013, first visited Rwanda in 2008 when he and his wife Jane Schmidthuber

Noah ’72 traveled there to recruit four students to study in Iowa. Since then, he has helped dozens of Rwandans study in the United States and encouraged U.S. colleges and universities to take students to Rwanda.

Beginning on April 7, 1994, the African country was devastated by a genocide against the Tutsi that is estimated to have killed up to 1 million people in 100 days. Despite the death and destruction of 29 years ago, Noah sees nothing but beauty and hope in a country he has now visited 35 times.

“The genocide against the Tutsi of Rwanda was brutal. The equivalent of the population of Waverly was killed every day, for 100 days, by clubs and machetes during the genocide. That is a terror no one here can visualize. People know this and have a hard time believing the country can be safe,” he said.

Dr. Brian McQueen, associate professor of sociology, has been interested in the country and the work it has done in the areas of gender equality and restorative justice since 2010. Shortly after coming to Wartburg, he was introduced to Noah and began planning a way to get Wartburg students to Rwanda. Several roadblocks, a global pandemic, and seven years later, he took his first May Term class in 2023.

“I’ve taken students to places to work with the most impoverished populations in the world. This time it was to work with people who had been victims of the second-largest genocide in the 20th century,” he said. “These are difficult things I ask the students to do, and they have to work very, very hard at it. To see them learning, how they are developing and changing, and how their lives are improving because of this is the big takeaway for me.”

The course started with a three-day peace and justice training through the Kigali Genocide Memorial that set the stage for nearly every experience that would follow.

“The training is based on restorative justice practices, which is an idea of how to restore society back to its functional state after bad things have happened. This is something that has worked amazingly well in different places, most notably Australia and New Zealand, but Rwanda is using it in a way that has never been done before,” McQueen said. “After the genocide, the training was seen as absolutely necessary because you had a society that was completely fragmented.”

Steve Noah’s ties to Rwanda

Steve Noah helped Kuder, a career guidance and educational consultant based in Adel, Iowa, launch the Rwandan Career Guidance Program in 130 secondary schools. The program, which was operational from 2012 to 2018, trained several hundred teachers and helped more than 35,000 students.

At the request of Ambassador James Kimonyo, who was the Rwandan ambassador to the U.S. in 2008 and is now the Rwandan ambassador in China, Noah assisted with the development of the Institute for Agriculture, Technology, and Education of Kibungo, now known as the University of Kibungo. Noah was invited back in 2016 to speak at commencement.

Noah now serves as the special adviser to the CEO of Aegis Trust, an organization working to prevent genocide through peace and values education. In Rwanda, the Trust manages the Kigali Genocide Memorial.

After the training, the students saw what they learned in action in one of the country’s reconciliation villages, where victims of the genocide live side-by-side with perpetrators of the same horror. But McQueen said it was more than just living next door to someone; the people in the villages work together to ensure everyone prospers. For instance, in Rwanda owning a cow is a sign of prosperity. The students met a woman who gave her cow’s calf to her neighbor, who also was a member of the family that murdered her family. The students also met a man and woman from opposite sides of the genocide who are now married and have children.

Dr. Debora Johnson-Ross, vice president for academic affairs, traveled with the group for several days, including during their visit to the village. An Africanist, Johnson-Ross has visited many African countries, but this was her first time in Rwanda.

“This experience was transformational for me to see those who were victims of the genocide living next door to those who were perpetrators and living in peace and cooperation with one another. They have not forgotten what happened to them, but they have made conscious decisions to live together in peace,” she said. “I think this is a model that is not typically seen. It speaks to the power of the individual to make a decision and then live out that decision.”

McQueen invited Olivia McAtee ’19 to join the group in Rwanda as a chaperone and to provide support during debrief sessions following the harder days. McAtee works in statewide prosecutions for the Iowa Attorney General’s Office, so seeing the restorative justice work firsthand was of great interest.

“We are seeing such a divide in our own country, so it was interesting to see the way they are working with each other and finding ways to bring some of those lessons home to my life and work,” she said. “I saw the importance of humanity while I was there, and I think I will definitely have a little more grace with people on all sides of the justice system after this experience.”

McQueen, who teaches courses in criminology and criminal justice, hopes the students also were encouraged by what they saw and are inspired to implement what they learned.

“This is still something I am trying to wrap my head around. I’ve seen it, so I know this kind of reconciliation exists, but I still don’t understand how you get to that point,” he said. “This experience was so important for our students, especially today. I believe we have a real problem in the United States, and we could really benefit from the work being done in Rwanda.”

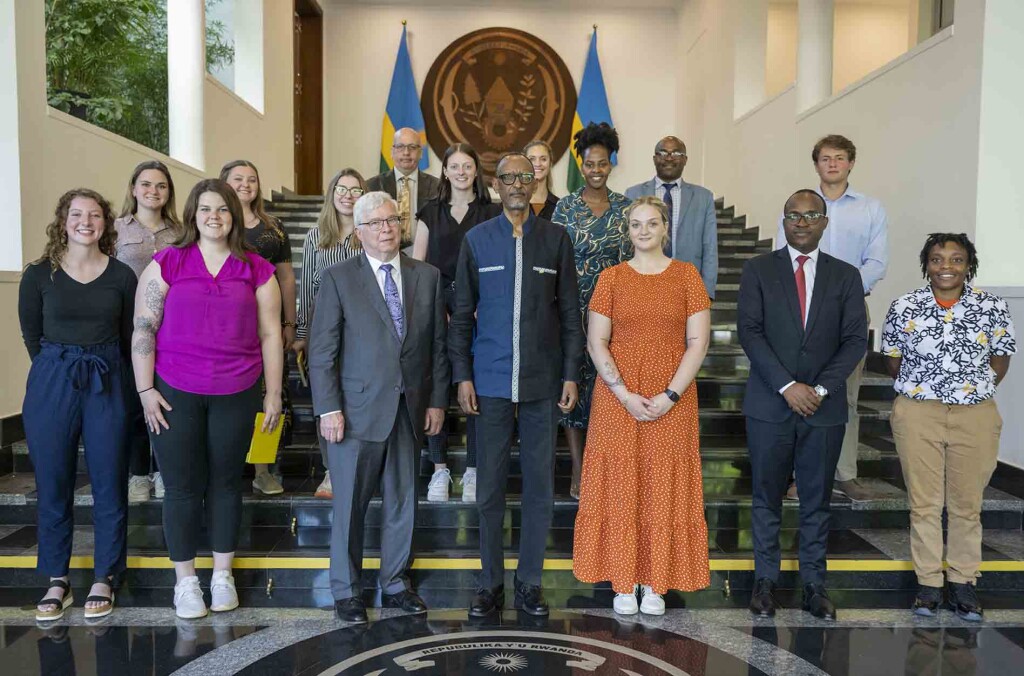

In addition to the training and reconciliation village visits, the students also learned about Rwandan culture, visited several genocide memorial sites, spent time in a traditional village, had an hourlong dialogue with President Paul Kagame, and met many other political and community leaders.

While Laurel Woodrum ’23 was impressed by all of the officials they were able to meet — “One doesn’t usually just visit and get to meet the president of a country” — it was an experience with Solid Africa that helped her focus on her future plans. In Rwanda, food services are not included in a hospital stay; instead, families are expected to fill that void.

When families are unable to provide for their loved ones, Solid Africa steps in to ensure patients receive the nutritious meals needed for their recoveries. The Wartburg team volunteered with the organization serving food at a hospital.

“That was a really eye-opening experience for me,” said Woodrum, who earned her degree in biochemistry and plans to enroll in medical school following a gap year. “The hospital was just like a big warehouse with curtains used to make makeshift rooms, but that was normal for them. That was a spark moment for me. I’ve always known I wanted to do some kind of outreach work as a doctor, but that was when I knew it was something that I would really like to pursue in the future.”

Woodrum wasn’t the only one called to service while in Rwanda. McAtee was particularly moved by her experience at the Groupe Scolaire Bare school, and upon returning to Des Moines, she started a fundraiser to cover the cost of school lunches for nearly 90 students for the

entire year.

“The kids there were all so full of joy and so appreciative of the things we brought them that day, and it was just some reusable menstrual pads for the girls and a guitar for the band. The whole school came out to welcome us and were cheering about the gifts. They were so excited about something that most of us take for granted,” she said. “When I learned that school lunches were something that they struggled with, talk about taking things for granted. If families here struggle to pay for school lunches, we have social programs that can help. They don’t. I figure many of us spend more than $60 a month on subscriptions, and that can pay for an entire year of lunches for

a student.”

McAtee knew she couldn’t afford to foot the entire bill, but using her network, she was able to raise more than $6,000 for the school.

“One of the very first weeks I was in this job at the Attorney General’s Office, someone said to me: ‘Evil sometimes prevails, but usually it doesn’t. Usually evil is overcome by good, but only if somebody works to generate the good,’” she recalled. “Positive things don’t just happen, but if you have the right people around you, you only have to put in a little effort to create the ripple effect. It was the community around me that believed we could help all of those students.”

After Johnson-Ross left the group in Rwanda, she traveled to Nuremburg, Germany. While there, she visited the Nuremburg Trial memorial at the Nuremburg Palace of Justice, where surviving World War II criminals were tried. Peace education is important there, too, but is done with a different approach. Since then, she’s been thinking of ways to connect what she experienced in Rwanda with what happened in Germany in a way that would allow Wartburg students to experience both.

“It would be an emotionally taxing course, but for students interested in social work, political science, or political psychology, it would be an interesting educational opportunity,” she said.

She’s also been ruminating on opportunities for Wartburg students in Rwanda and Rwandan students at Wartburg, a dream that Noah has had for decades.

“Jane and I jumped on this roller coaster nearly 20 years ago. Since then, I’ve met people who are now like family to me,” Noah said. “I would love for more students at Wartburg to experience even a fraction of that so that they can begin to love this place like I do.”